What Truly is Punk Nowadays? + A Look at Vivienne Westwood's Contributions to Punk Fashion

Vivienne Westwood built a revolution out of seams and sex—but what happens when rebellion becomes just another outfit? This is the real story of punk’s rise, its commodified collapse, and what true re

The Origin Myth — Vivienne Westwood, 430 King's Road, and the Birth of Punk

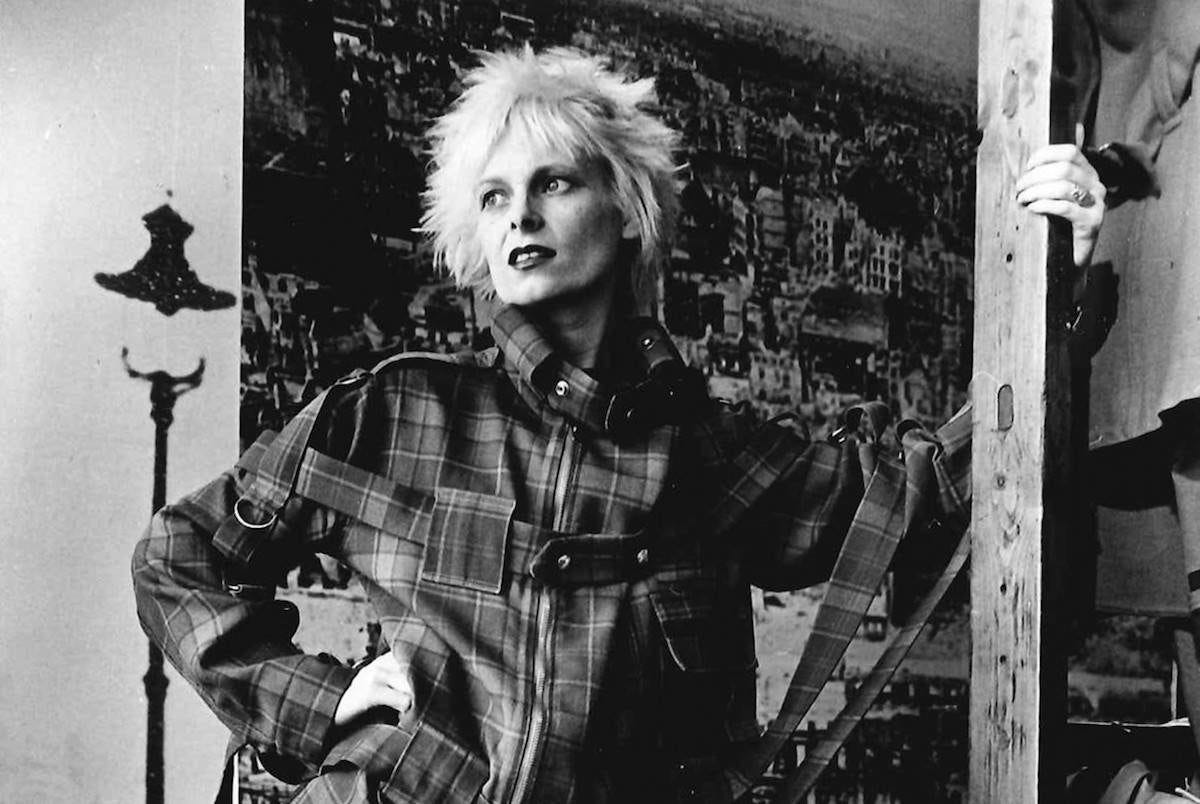

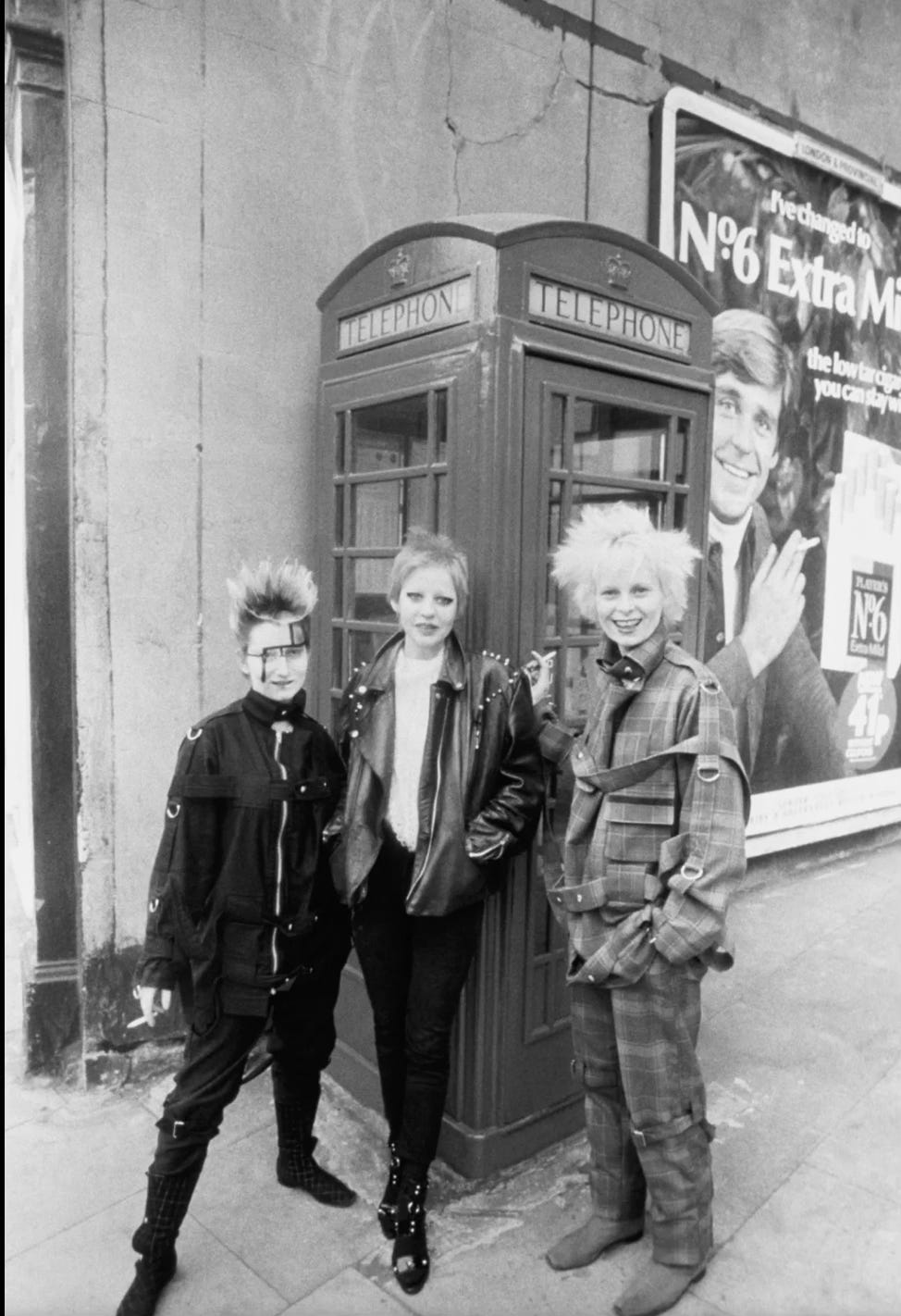

There’s something mythic about Vivienne Westwood that time hasn’t been able to sterilize. Maybe it’s the way she made fashion dangerous. Or how she conjured subversion from seams, made sex look like resistance, made a t-shirt capable of getting you arrested. But the real beginning—the dirty, electrified origin—wasn’t on a runway or in a glossy spread. It was on a London street, in a tiny shop with a name that kept changing: “Let It Rock.” Then “Too Fast to Live, Too Young to Die.” Then simply, “SEX.”

By the time it was renamed “Seditionaries,” the boutique at 430 King's Road was already pulsing with something radical. The clothes weren't just clothes. They were weapons. Designed by Westwood and her then-partner Malcolm McLaren, they embodied a philosophy that spit in the face of the British monarchy, sexual repression, and middle-class respectability. They weren’t designed to be “beautiful.” They were designed to piss people off. To make you stare. To make you think.

The boutique wasn’t just selling garments—it was selling a worldview. Bondage pants, razor blade necklaces, dog collars, inside-out sweaters, trousers cut so low the pubic bone was practically mandatory viewing. Shirts screenprinted with images of semi-nude cowboys or collaged Nazi insignia—part provocation, part political satire—were designed to offend. And it worked. People were shocked, enraged, inspired. And that emotion—that raw nerve—was the whole point.

This was the 1970s: the UK economy was a mess, youth unemployment was high, and the monarchy was still a sacred cow. The Sex Pistols, under McLaren’s curation, became Westwood’s fashion mascots—particularly Johnny Rotten, whose sneer and shredded shirts captured a generation's fury. “Punk,” as we understand it, wasn’t born from sound alone. It was sewn into fabric, built into boots, screamed onto skin.

As Pace University’s 2021 Honors College thesis on punk fashion explains, Westwood “used clothing as a tool to communicate social discontent,” her designs “flaunting taboos and rewriting social codes.” This wasn’t fashion as we knew it. It was fashion as insurgency. It was fearless. And crucially, it was deeply anti-commercial—at least at first.

There’s something sacred about that original era of punk. Something that feels almost impossible to replicate now. It was messy. Ugly. Not curated for an audience. Not repackaged for resale. It wasn’t performance art or Tumblr nostalgia. It was life or death. “The punk movement wasn’t supposed to be fashionable,” Westwood later said. “It was about real politics.”

But that didn’t last.

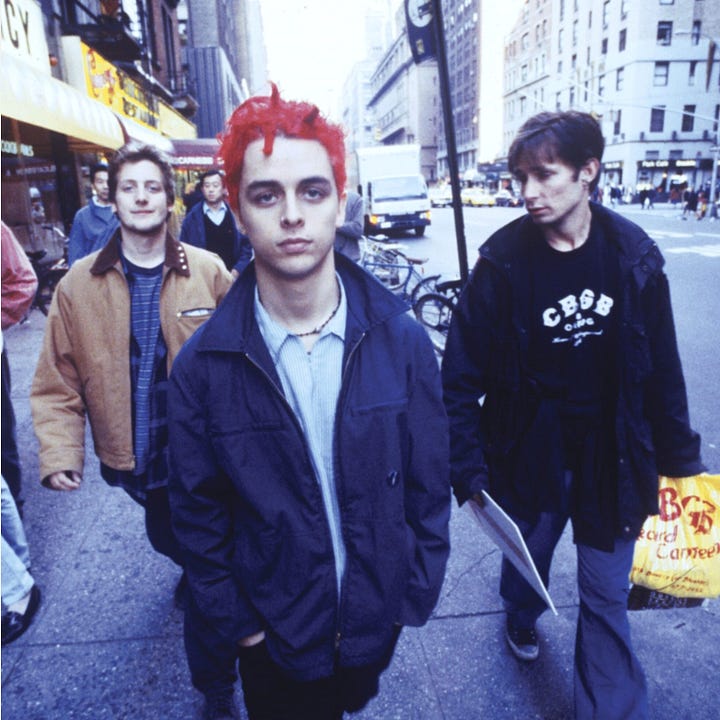

As we crossed into the late 80s and 90s, the world caught on to punk’s aesthetic. It started to show up on the runways it once raged against. Luxury brands dabbled in leather and plaid; safety pins went from symbol of poverty to pricey accessory. By the time Avril Lavigne was selling studded belts at Hot Topic in 2002, punk had been fully commodified. What had once been dangerous was now digestible. Sanitized. Sold at the mall.

And this—this is where things start to get complicated. Because if punk was always meant to be anti-establishment, what happens when the establishment co-opts the look?

In that context, Westwood’s own evolution becomes a mirror. She shifted too—from radical streetwear into couture. By the late ‘90s, she was designing corsets and taffeta gowns. But her ethos never really softened. She said, repeatedly, that fashion could still be political. Her runway shows called out climate change, corporate greed, Brexit. “Buy less, choose well, make it last,” she told the BBC in 2011, in an almost anti-capitalist soundbite masquerading as style advice.

Still, it’s worth asking: is choosing to dress punk today—leather jacket, plaid skirt, microbangs and platform boots—an act of rebellion? Or is it just… a fashion choice?

The answer depends on what you believe punk truly is.

Is it the uniform? Or the mindset?

Because today, that same shredded look is mass-manufactured, sold on ASOS and Instagram storefronts. You can get a Westwood-style orb necklace for $15 on Depop. You can cosplay 1976 London from your bedroom in Ohio. But is it punk?

Or is it a nostalgic tribute to something that once was?

“The thing about punk is that it was never supposed to last,” one Reddit user wrote on r/punkfashion. “It was a scream, not a legacy.”

So then maybe that’s the point. Punk, if it is anything anymore, can’t be preserved in amber. It can’t be performed. It has to respond. It has to evolve.

Because rebellion can’t be replicated. It has to be real.

And if punk today looks exactly like punk in 1994… maybe it’s already dead.

But maybe—just maybe—it’s also being reborn in ways we don’t recognize yet. In forms we haven’t named. In aesthetics that feel like the opposite of punk but carry the same spirit. Not in spiked hair or anarchy symbols. But in unfiltered self-expression, in political art, in genderfuck makeup, in choosing softness in a brutal world. Maybe even in radically boring clothes that reject the pressure to “be seen” at all.

But that’s getting ahead of ourselves.

First, we have to mourn the old punk. To understand what it was before we can name what it’s becoming.

And for that, we have to return to Westwood—her tartan, her troublemaking, her unmatched rage—and ask: what does it mean to create something that resists everything, even its own legacy?

Aesthetic Decay — How Punk Was Packaged, Sold, and Stripped of Its Bite

By the time punk fashion showed up on the racks of Urban Outfitters, its rebellion had been put on a leash.

In the decades since Westwood’s bondage trousers and blood-red tartans lit a cultural fuse, the look of punk has undergone a disturbing transformation. What began as an urgent form of social commentary has been flattened into an aesthetic—stripped of context, mass-produced, and algorithmically optimized for clicks. Somewhere between the Sex Pistols and TikTok, punk stopped being a threat and became a trend.

This isn’t a new story, but it’s still a painful one. Capitalism is a master cannibal—it consumes the very movements that oppose it, chews them up, and spits out versions that are palatable enough to sell. And punk, for all its fury, was no match.

The commodification of punk didn't just dilute its message—it actively severed the political from the visual. In the hands of the mainstream, symbols of protest became empty signifiers. The safety pin, once a desperate DIY repair or a visual middle finger to societal norms, is now a Pinterest accessory. Leather jackets are sold pre-distressed. Fishnets and tartans are manufactured by fast fashion empires that exploit the very working-class people punk once defended.

“Punk became an aesthetic before it had the chance to finish its sentence,” wrote fashion critic Giulia Mensitieri in The Most Beautiful Job in the World, her ethnographic analysis of exploitation in fashion’s creative industries.

By the late 1990s, punk’s image was no longer underground. It was editorial. Vivienne Westwood’s own designs became high fashion, shown in gilded palaces and worn by aristocrats. It’s a paradox that would haunt her legacy: the queen of punk was eventually given a damehood by the British Crown.

But Westwood never played dumb about the contradiction. She actively leaned into it. To her, using fashion’s own system—its wealth, its visibility, its spectacle—as a weapon was itself an act of rebellion. In interviews, she insisted that working within the industry didn’t mean she had lost her edge. “The only reason I’m in fashion is to destroy the word 'conformity,'” she told i-D Magazine in 2004. “Nothing else matters.”

So what happens when everyone is punk? When you can buy anarchy at Zara?

The democratization of subculture through social media and fast fashion has made it easier than ever to look like you belong to a movement. But it’s also made it harder to mean it.

This is where the idea of performance enters the conversation.

To dress punk in 2025 is no longer shocking. It’s often nostalgic, sometimes curated to a fault, sometimes even ironically conservative. You’re not going to get kicked out of a restaurant for wearing a plaid skirt and combat boots. No one’s clutching their pearls over your chain choker. The look is recognizable, safe, and—ironically—socially acceptable. It no longer pushes boundaries. It references the people who once did.

And that’s the crux of it: a reference is not a rebellion.

TikTok creator @neutralmilkhotelgirl summed it up in a viral video: “People treat punk like a costume now. Like, you can dress punk and still be super neoliberal, super invested in the system. It’s an aesthetic, not a politic.”

We’ve entered an era where authenticity is filtered through algorithms, and rebellion is often indistinguishable from branding. Punk’s visual code has been absorbed into mainstream fashion, where it sits alongside cottagecore, coquette, and “clean girl” as just another style on the carousel.

But there’s another tension here too—one that lives under the surface of Instagram mood boards and punk playlists on Spotify. It’s the question of whether true rebellion can even be visual anymore. Or if, in the age of hyper-visibility, the real rebellion is refusing to be seen at all.

Because what if dressing punk today is less about actual defiance and more about looking like someone who defies? What if it’s cosplay?

Not everyone who dresses punk is performing. But we have to admit that the default cultural meaning of punk has changed. Wearing a Westwood orb choker doesn’t carry the same charge it once did. Not because it’s bad, but because culture evolves. It’s been absorbed. The aesthetic has lost its ability to provoke. And in some ways, that’s a good thing. It means society has moved forward, become more accepting of difference. But it also means that what once felt risky, dangerous, and deeply alive has been declawed.

So where does that leave us?

What does it mean to dress punk now, in a world where the original codes have become fashion shorthand?

Is it still punk to rebel against the mainstream—if the mainstream is already selling your rebellion back to you?

Or is that just a game of mirrors, a cycle of retro references that never moves forward?

The truth is, if punk was ever about anti-establishment energy, then it must change every time the establishment does. That means punk cannot stay frozen in time. It must shapeshift. It must disintegrate and reassemble. It must feel uncomfortable again.

“If you want to be punk in 2025,” said cultural critic Shon Faye on her podcast Call Me Mother, “you need to find the new thing people are scared of. And it’s probably not a studded belt.”

This doesn’t mean throwing away the legacy of Westwood or the early punks. It means understanding that the uniform they created is now a museum piece. Revered. Beautiful. But not radical.

Radical is what comes next.

Radical is what no one’s ready for yet.

Radical doesn’t ask for permission.

And maybe—just maybe—that’s where the new wave of punk is already beginning.

Post-Punk Possibility — If Everything’s Been Done, What’s Left to Rebel With?

Punk, as we knew it, is a ghost. But maybe that’s the point. Maybe the afterlife of punk is where things get interesting.

In a world where the visual language of punk has been so thoroughly cannibalized, rebellion doesn’t look like it used to—and maybe it shouldn't. The safety pins have lost their teeth. The tartan is archival. And the act of flipping off the Queen doesn’t hit the same after Vivienne Westwood became a Dame.

So what now?

Here’s where we have to stretch. To stop thinking of punk as a fixed aesthetic and start thinking of it as an evolving practice. A mode of existence. An ethic. Not “what you wear,” but how you live.

Because let’s be real: trying to shock people with your outfit in 2025 is like trying to surprise someone on the internet. It’s already been done. We’ve seen it. We’re past it. The new frontier isn’t visual disruption—it’s ideological. Emotional. Subversive in ways that aren’t always visible.

As author and culture critic Bell Hooks once said: “The function of art is to do more than tell it like it is—it’s to imagine what is possible.”

And that’s what the new punk is about. Imagination. Not just resistance, but radical reimagining. Of gender. Of value. Of selfhood. Of beauty. Of systems.

Take, for instance, punk’s relationship to gender. Where the 70s punk scene opened the door for gender nonconformity—through smeared lipstick, kilts on cis men, and sexual ambiguity—the 2020s have blown the hinges off. Artists like Ethel Cain, Yves Tumor, and Arca aren’t just playing with presentation—they’re living at the blurry edges of identity. This isn't about shock for shock’s sake. It's about truth, even when that truth is uncomfortable, chaotic, or illegible to the mainstream.

Because being anti-establishment in an era where everything is content means resisting the pull to perform at all.

This is the new frontier: anti-performance.

It’s refusing to play.

Of course, the echoes of old punk are still valuable. Westwood’s legacy remains crucial—not because we should recreate it, but because we should understand what made it work. She used fashion as a political scalpel. She refused compromise. She made the world feel uncomfortable, and then used that discomfort as leverage.