Sacred, Spoiled, and Strange: The Dark Symbolism of Milk

A symbol of purity that curdled into something far more complicated.

written by Melissa McNair

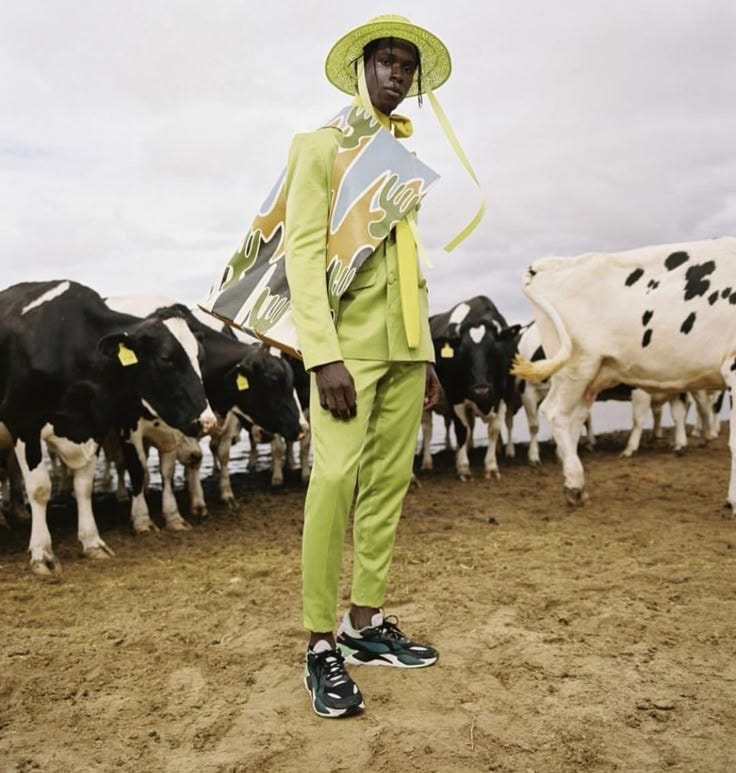

Photography by Charlotte Roy Rose

I. Milk as Offering: Origins of a Sacred Substance

Long before milk became part of breakfast, it was part of something bigger—rituals, prayers, and offerings to the gods.

In Ancient Egypt, milk had deep spiritual meaning. The goddess Hathor, often shown as a cow or a woman with cow horns, was believed to feed the pharaohs with her milk. This wasn’t just a nice story—it was a way to say that rulers got their power from something divine. The milk was more than food. It was proof that a ruler was chosen, cared for, and made sacred by the gods.

Other ancient cultures saw milk the same way. In Sumerian temples, people would pour milk over statues of their gods. This wasn’t to feed them, but to show devotion and give back something precious. In early Indian (Vedic) rituals, milk was poured into sacred fires. The fire was seen as a messenger to the gods, and the milk was an offering meant to bring blessings or protection in return.

Even old Greek and Roman stories used milk to explain big, strange ideas. One myth says the stars of the Milky Way were created when the goddess Hera pulled her breast away from the baby Heracles, and her milk spilled across the sky. It’s dramatic, even violent—but that’s the point. In these stories, milk wasn’t soft or comforting. It was powerful. Cosmic. Bigger than life.

The common thread across all of this is that milk was seen as a gift from nature—something alive, something that came from a body. Giving it back to the gods was a way of saying: We honor where we came from. We trust that life gives back when we give first.

Today, we think of milk as a product. Something bought and stored in the fridge. But in ancient times, it was more like a sacred exchange—a liquid bridge between people and the divine. It wasn’t just about survival. It was about connection, meaning, and trust in a world filled with mystery.

II. Witches and Spoilage: When Milk Became Dangerous

As much as milk was once treated as sacred, it also became something people feared.

In early modern Europe—especially from the 1500s through the 1600s—milk was at the center of many witchcraft accusations. These weren’t random. Milk was tied to nature, fertility, and women’s bodies, and when something went wrong with it—if it spoiled too fast, if a cow stopped producing, if butter wouldn’t churn—people often blamed a witch.

These beliefs weren’t based on science. They were based on anxiety. People lived close to the land, and they depended on milk for food and income. So when something disrupted that, it felt personal—and supernatural. If a cow’s milk dried up, someone must have cursed it. If milk turned sour too quickly, maybe someone with bad intentions had passed by. These weren’t just old superstitions—they were attempts to explain why things broke down in a world without answers.

What’s striking is how often these fears centered on women. Witches were mostly women, and milk was seen as a female substance—something tied to the body, to motherhood, to the home. In many trial records, women were accused of “stealing” milk from their neighbors’ cows or bewitching butter churns. In one famous Scottish case, a woman was said to have created a magical rope that, when shaken, would cause milk to pour out as if from nowhere.

These stories might sound absurd now, but they reflected a very real fear: that the natural order—birth, nourishment, care—could be hijacked. That something as gentle as milk could be twisted into a source of control.

In a way, milk became a symbol of what people feared most: the loss of control over the everyday. When milk went wrong, it meant something had gone wrong in the world. And in a culture that already distrusted powerful or independent women, it wasn’t hard to point fingers.

That fear still lingers, in subtle ways. Even today, we’re uneasy about spoiled milk. It smells bad, turns sour, and feels wrong in a way that other foods don’t. It’s more than just unpleasant—it’s unsettling. Like something pure has betrayed us.

III. Alchemy and Purity: Milk as a Symbol of Spiritual Transformation

If earlier cultures saw milk as a gift or a threat, mystics and alchemists saw it as something else entirely: a signal of transformation.

In alchemy—the medieval blend of science, philosophy, and spiritual belief—milk didn’t just symbolize life. It stood for a specific stage in the journey toward enlightenment. Alchemists divided transformation into several phases, and one of them was called the albedo, or “whitening.” It came after the dark, chaotic beginning (the nigredo) and before the final state of unity and perfection (the rubedo, or reddening).

Albedo was the cleansing phase. A stage of purification, when the soul—or substance—was being stripped of corruption. The whiteness of milk made it a perfect metaphor. It was soft, flowing, full of potential, but also empty of impurity. Not yet perfect, but no longer broken. In this framework, milk wasn’t the goal. It was the turning point. The in-between.

This idea showed up in religious visions too. In the 12th century, the Christian monk Saint Bernard of Clairvaux wrote about a dream in which the Virgin Mary leaned over and fed him her milk. That image wasn’t meant to be taken literally. For him, her milk symbolized divine wisdom, something passed from the sacred into the human mind. It was nourishment for the soul—not the body.

Even outside religion, this idea that milk was more than a substance lingered. In some medieval medical texts, milk was said to be “white blood”—the cleaner, calmer version of the fluid that gives life. Blood was associated with violence, injury, and passion. Milk, by contrast, stood for peace, recovery, and inner cleansing.

But there’s a tension here. Milk was pure, but not final. It was the clean slate, not the masterpiece. That’s why it feels fragile—because it exists between extremes. It comes from the body, but it’s not quite bodily. It looks clean, but it spoils fast. It nourishes, but can also curdle. In both mystical and literal terms, milk holds power because it sits in transition—between corruption and perfection, between birth and decay.

That’s why it shows up so often in stories of change. Whether it’s saints, sorcerers, or seekers of truth, milk keeps reappearing at the moment before something shifts. It marks the space where something is being wiped clean—right before it becomes something new.

IV. Modern Milk: From Nurture to Unease

In the modern world, milk has kept its symbolic weight—but it’s changed sides. It no longer feels safe or sacred. In media, it often shows up when something is wrong beneath the surface.

Take Jordan Peele’s Get Out. There’s a moment when the character Rose, a seemingly sweet white woman, eats dry cereal one piece at a time while sipping milk from a glass. It’s a quiet scene, but it’s deeply disturbing. The separation of the milk from the cereal mirrors the way she separates emotion from action. She’s calm, clinical, and in control—while her family is trapping and destroying people. The milk isn’t comforting. It’s sterile. Cold. Almost clinical. It says everything about her obsession with purity, control, and performance.

Another example is Hans Landa in Inglourious Basterds. When he interrogates a French farmer hiding Jews under the floor, the first thing he does is pour himself a tall glass of milk and drink it slowly. He’s polite, well-mannered—and terrifying. The milk isn’t innocent. It signals that he’s in charge. That he feels at home in someone else’s house. That he can smile while doing something unspeakable.

These scenes don’t work because milk is strange on its own. They work because milk carries centuries of meaning—motherhood, purity, devotion. And when a character drinks it coldly, without warmth or care, it clashes with everything milk is supposed to be. The effect is unnerving because it’s symbolic betrayal. A sacred substance, used by someone who has no soul.

Even in advertising, there’s a gap between what milk is supposed to mean and how people really feel about it. Campaigns like “Got Milk?” tried to bring back the old comfort—wholesome, clean, family-friendly—but they never quite succeeded. Many people are physically intolerant of milk. Others avoid it for ethical or environmental reasons. For something once seen as a divine gift, it’s become surprisingly controversial.

And yet—milk keeps showing up. Not just as a drink, but as a visual cue. It’s still used in horror, in surreal art, in fashion campaigns, in perfume ads. It still represents something soft, white, and supposedly pure. But the emotion behind it has shifted. Now, when we see milk in the wrong hands, it feels like a warning. Something is about to break.

Why? Because we still remember—maybe not consciously, but culturally—that milk used to mean everything good. Life. Safety. Nourishment. So when it’s used by someone cold or violent, the betrayal cuts deeper.

That’s what makes milk so powerful in modern storytelling. Not because of what it is—but because of what it used to be.