Jennifer’s Body and the Monstrous Feminine

An analysis of the film Jennifer’s Body, specifically its commentary and themes on trauma, patriarchy, and the horrors of girlhood.

Written by Michaela Smith

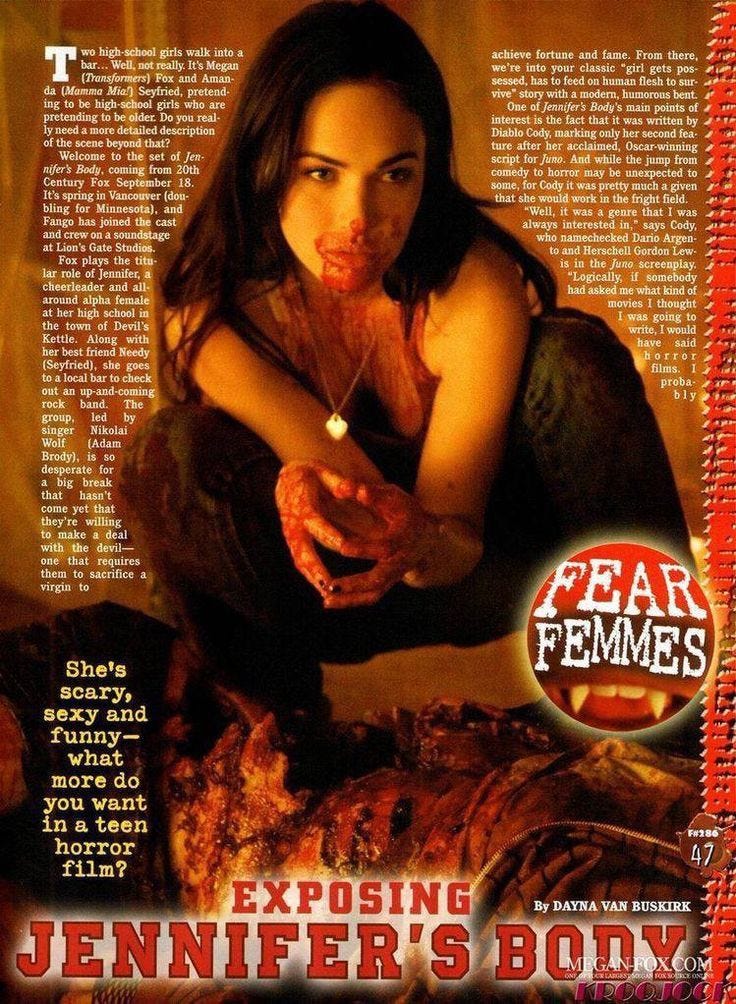

“Hell is a teenage girl” is the first line spoken in the horror film Jennifer’s Body. Made in 2009, the film was panned by critics, due in part to the misleading marketing campaign capitalizing on Megan Fox’s status as a sex symbol, catering to the male audience that found her in Transformers instead of women.

Over the years, Jennifer’s Body has become a cult classic among audiences, especially women, as the film’s themes and commentary were ahead of its time.

Directed by Karyn Kusama, Jennifer’s Body is a feminist horror-comedy that follows Jennifer Check, a popular girl who transforms into a demon with a taste for human flesh, hunting her male classmates. Conflicted, Jennifer’s best friend Needy must find a way to stop her killing spree.

Like other horror films, Jennifer’s Body uses a fictional monster to represent and confront the fears and anxieties that audiences have regarding a specific issue or topic.

However, the film separates itself by addressing issues that women face, especially teenage girls, including the effects of trauma, patriarchal standards, and toxic friendship.

By establishing a woman as the monstrous figure, Jennifer’s Body confronts our fears surrounding gender and is an allegory for trauma.

(Disclaimer: Mild spoiler warning ahead, as I will be discussing major plot points from the film. In addition, a trigger warning for the brief mention of sexual assault.)

Part 1: “She’s Evil, and not just High School Evil”: What Makes Jennifer’s Body a Horror Film?

What elements does Jennifer’s Body have that makes it a horror film? How does it fit within and divert from the genre?

The film features many of the classic horror tropes, including the final girl, encounters with the monster, and a rising body count of victims. But Jennifer’s Body reinvents many of these tropes, specifically that of the monster.

In a traditional horror film, Jennifer checks all of the boxes as the first victim, a pretty girl oblivious to the danger around her before she is killed in the opening sequence.

However, Jennifer’s Body is not your traditional horror film: Jennifer becomes the monster to haunt and wreak havoc on her town, mainly the boys at her school.

But the film is not black-and-white, as it explores the gray area surrounding Jennifer’s character. She is not one-dimensional, as her character is designed to be complex. The film paints Jennifer as both a victim of patriarchal violence and a vengeful monster who preys on boys.

Back to the victims: throughout the history and development of the horror genre, women have predominantly been the victims, with the camera lingering on their final moments. However, Jennifer’s Body flips this trope on its head, as a majority of the victims in the film are men.

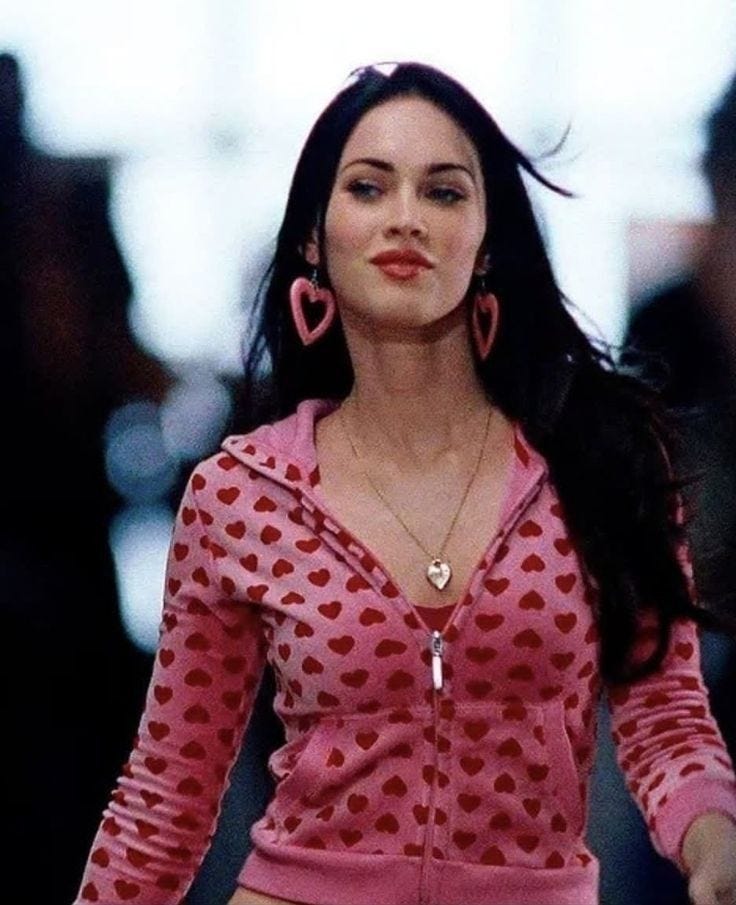

Jennifer is charismatic and eye-catching, her outfits capturing the attention of audiences and boys alike. She is a siren, luring male victims into her trap.

In a similar way, the film lures the audience into the story using flashbacks, as the film is mostly told from the perspective of Needy, Jennifer’s best friend. In addition, Jennifer’s Body is a masterclass in costume design, showcasing the contrast between Jennifer's personality and demonic transformation, with bright pink colors and low-rise jeans, reminiscent of the 2000s.

These elements represent the male gaze, luring the audience in, then subverting expectations, forcing them to confront the destructive effects of trauma and the intersection between femininity and monstrosity.

Part 2: The Cycle of Trauma

Jennifer’s Body is self-aware and reflexive, making note of patriarchal standards through the portrayal of Jennifer.

Jennifer is painted as the dream girl: girls want to be her and the boys want to date her. She is attractive, assertive, and aware of the effect that she has on people, including her best friend Needy.

At the beginning of the film, Jennifer and Needy go out to a nearby bar to see Low Shoulder, an alternative band perform.

As the band performs, Jennifer appears to fall under a trance, as the bar slowly begins to catch fire.

Amidst the screaming patrons, Jennifer and Needy manage to escape the bar. As they try to process the traumatic event, both girls encounter the lead singer, who leads Jennifer into the band’s van.

Jennifer, still catatonic, steps into the van, surrounded by the other band members. Through a point of view shot, we see the situation from Needy’s perspective, making eye contact with Jennifer, powerless as the van door closes.

Later that night, Jennifer returns to Needy’s house, looking like a complete shell of herself. She smiles creepily, with blood running down her white jacket that is torn and disheveled.

As the audience, we can infer that something terrible has happened to her, but we don’t know what.

It isn’t long until we see Jennifer killing her first victim in a forest, the majority of the violence occurring offscreen. We see Jennifer killing her male classmates, but we never get an explanation as to why.

At the halfway mark of the film, we learn how Jennifer became a man-eating demon. Jennifer sneaks into Needy’s bedroom as she recounts what happened the night that she was taken by the band.

In the only flashback from Jennifer’s perspective, we learn that the band intends to sacrifice her to the devil for fame and fortune, believing that she is a virgin.

The scene is distressing and uncomfortable, as Jennifer is pleading for her life, all while the band surrounds her, remaining apathetic and cold.

In his essay “An Introduction to the American Horror Film,” film critic Robin Wood cites that “the dominant images of women in our culture are entirely male-created and male controlled.” Jennifer is both physically and metaphorically restrained by the male gaze.

We see Jennifer’s fear on full display, as tears stream down her face and her lip quivers. Another disturbing aspect of the scene is that the band sings to Jennifer moments before they are about to kill her, symbolizing Jennifer’s continued objectification.

The band does not see her as a person, but simply a stepping stone for them to achieve their goals. The camera shakes as the lead singer stabs Jennifer, creating an unnerving atmosphere as we hear her screaming.

Additionally, the scene uses a combination of high and low angle shots, demonstrating a power dynamic between Jennifer and the lead singer.

In her essay “I Eat Boys: Monstrous Femininity in Jennifer’s Body,” Victoria Santamaria Ibor asserts that “Jennifer is not sexually assaulted in Jennifer’s Body, but the use of reaction shots of Nikolai above her as he thrusts his knife inside her body while she suffers below him can be read not only as a murder but a metaphorical rape” (Santamaria Ibor 155).

Jennifer’s violent death at the hands of the band can be read as an act of sexual assault, especially considering that she is stabbed in the stomach. However, I understand that others may interpret the scene differently.

Unbeknownst to the band, Jennifer is not a virgin, and the sacrifice goes wrong. While the band face no consequences, Jennifer becomes possessed by a demon, doomed to consume human flesh forever.

As a result, Jennifer must feed on humans in order to survive and remain youthful. When she does not feed, her eyes become sunken and she grows tired.

The act of Jennifer luring and cannibalizing her male classmates contains two different metaphors. In a way, Jennifer eating boys represents a reclamation of her power, consuming the boys that view her as an object.

However, this act of consumption feeds into the patriarchal standards that dictate how women should live. In the eyes of the patriarchy, women should cater to and make themselves more appealing to men.

Part 3: Hell is a Teenage Girl: Jennifer & Needy

One of the most important aspects of Jennifer’s Body is the relationship dynamic between Jennifer and Needy. Best friends since kindergarten, both girls are tight-knit and spend most of the film together.

At the beginning of the film, Needy acknowledges that at first glance, their friendship seems unlikely, referring to herself as a “dork” and Jennifer as a “babe.” Both girls are polar opposites of each other: Needy is reserved and sincere, while Jennifer is extroverted and charming.

Although their friendship appears genuine, there are moments where their connection borders on toxic and controlling. In a montage scene, Needy is trying on different outfits for the bar, stating that her outfits should not upstage Jennifer.

Needy eventually settles on a tank top layered over a T-shirt, while Jennifer wears a low-cut leopard print top that accentuates her cleavage.

After Jennifer becomes a demon, she grows more hostile towards Needy, criticizing her appearance and gaslighting her, especially when Needy begins to suspect that Jennifer is behind the town killings.

This conflict between Jennifer and Needy comes to a head in a climactic scene, where Needy confronts Jennifer about how she has treated her. Needy strikes a nerve when she calls Jennifer “insecure,” to which Jennifer fires back saying that she is “still socially relevant.”

In an offhand remark, Needy replies “when you didn’t need laxatives to stay skinny,” instantly sending Jennifer into a rage. This simple line speaks volumes, as it echoes the patriarchal standards to remain youthful. Jennifer feels pressured by society to remain thin and beautiful, but will always be chasing perfection, never satisfied.

Additionally, Jennifer and Needy’s friendship represents the competition between women fueled by patriarchal beauty standards, tearing each other down instead of building each other up. This unnecessary competition and hostility turns women into monsters, hungry for validation and approval from the male gaze.

Conclusion:

Jennifer’s Body is one of my favorite films, as it is layered with symbolism and becomes more relevant every time I watch it. The film addresses the issue of patriarchy and unrealistic beauty standards, especially with teenage girls.

More importantly, Jennifer’s Body is a reflection of society, turning a mirror to the audience, forcing us to confront our internal biases and emotions. To what extent do we demonize ourselves and other women, and in what ways are women demonized in the media?

How can we combat these patriarchal standards and toxic competition? By building community and fostering meaningful connections with each other, rooted in unconditional love, inclusivity, and celebration of the feminine experience.

About the Author:

Michaela Smith is a recent college graduate who enjoys writing poetry and watching video essays.

Instagram: @michaela_s.23

Substack: @luckymuse