From Freak Shows to TLC: Dissecting Our Human Addiction to Spectacle

The sideshow never died — it just got a reality TV slot. What our obsession with difference really says about us.

The 19th-century freak show never really ended. It just stopped asking for a ticket. Today, it plays out on cable television — framed as reality, disguised as empathy, repackaged as education. Its most successful incarnation lives on TLC, a network that began as The Learning Channel but has since evolved into a rolling archive of human difference presented for public consumption.

This is not a surface comparison. The connection between 19th-century freak shows and modern-day reality television is not metaphor. It’s lineage. To understand what we’re really watching when we stream My 600-lb Life or Extreme Sisters, we have to go back to the original tent, to the people inside it, and to the minds watching from the outside.

The Tent, the Body, the Transaction

To understand the freak show, you have to understand its economics. The 1800s were the golden age of the American sideshow. At its center: Phineas Taylor Barnum, the self-proclaimed “Prince of Humbugs,” who understood something about human curiosity that no scientist could measure. People weren’t drawn to deformity. They were drawn to narrative. Tragedy, miracle, rarity, survival.

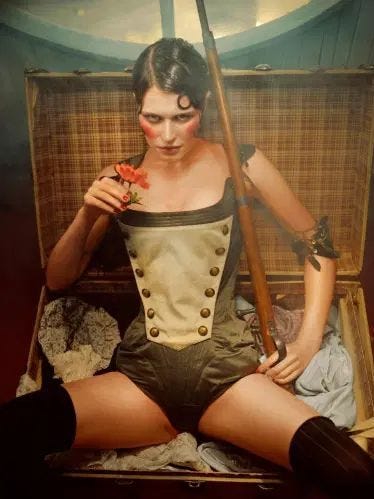

Barnum didn’t just display bodies. He invented personas. Charles Stratton, who was born with dwarfism, became "General Tom Thumb," a fabricated military figure who toured Europe like royalty. A formerly enslaved man with albinism was billed as a "living curiosity." Barnum created backstories, scripts, costumes. Audiences weren’t paying to see a person. They were paying to witness a contradiction: a child who looked like a man, a woman with a beard, conjoined twins who danced in sync.

The performers, often poor, disabled, or outcast, had few options. Some profited from the attention. Many didn’t. Most lived within the confines of performance schedules and gaze. They were not simply viewed. They were consumed.

And behind the curtain? Wealth. Barnum's exhibitions pulled in thousands per day. The freak show was one of the earliest models of scalable, profitable spectacle — not in spite of ethics, but in deliberate defiance of them. It was the monetization of discomfort, disbelief, and unspoken relief: thank God I’m not them.

From Sideshow to Syndication

TLC's modern programming functions on the exact same emotional economy. Its viewers are offered access to lives framed as extreme: unusual medical conditions, family structures, addictions, and lifestyles. But what's actually being sold is a chance to feel safe in one's own life.

Shows like My 600-lb Life follow a rigid formula: humiliation, breakdown, surgery, redemption. But in practice, most of these stories aren’t about healing. They’re about surveillance. We see what the subjects eat, how they bathe, how they are lifted from their homes. Their bodies are dissected in camera shots no less violating than 19th-century gawking.

In I Am Shauna Rae, a cancer survivor frozen in childlike proportions navigates adulthood under public scrutiny. In MILF Manor, mothers and sons are placed in a dating show together. The pitch is absurd. The point is discomfort. Audiences are expected to oscillate between disgust, fascination, and laughter. Ratings spike accordingly.

These are not documentaries. They are pageants of control, edited to maximize alienation. What TLC teaches is not understanding. It teaches us how to look without blinking.

Not Psychology — Power

The standard explanation for why we watch these shows is psychological: escapism, comparison, schadenfreude. But that language feels too clean. It lets us off the hook.

We don’t just watch because it makes us feel superior. We watch because it reaffirms the borders of acceptability. Because these shows place someone firmly on the outside and, in doing so, keep us inside. The subjects become social landmarks. If they are what is strange, we must be safe.

This is not an accident. TLC operates on a deep understanding of social control. Its shows flatten lives into archetypes: the hoarder, the addict, the obese person, the girl trapped in a child's body. But in that flattening, the network preserves a kind of moral order. There is us — viewers, stable, watching from clean couches. And there is them — unstable, excessive, requiring intervention.

What is being regulated here is not just behavior. It’s value. Worthiness. Watchability. TLC frames itself as inclusive, but it’s a machine that quietly reestablishes the center by relentlessly showing us the fringe.

The Digital Tent

Freak shows used to be temporary. You went to the edge of town, paid your coin, saw the show, and left. Now the tent is permanent. It lives in our phones. It updates weekly.

Reddit threads mock and mourn these people in equal measure. TikTok clips reduce entire lives to soundbites: a mother breastfeeding her child until age 9; a woman married to a ghost; a sister who insists on bathing with her twin.

What we’re seeing is not eccentricity. It’s algorithmic pathology. TLC doesn't just showcase these stories. It creates them, selects the most exaggerated versions, edits them for viral moments, and packages them as truth. This isn't reality. It's manufactured unreality, engineered for maximum reaction.

The Gaze That Never Blinks

There’s a reason the freak show never disappeared: it works. It works because it gives form to our fears. It lets us look at what we think is failure, deviance, excess, and place it safely outside ourselves. It soothes us by reminding us who we are not.

But the cost is real. Not just for the people who agree to be filmed, but for the audience who learns, over time, that dignity is negotiable, that difference is spectacle, and that the worst thing you can be is unwatchable.

The freak show did not die. It evolved.